Before I met my husband, I was a defiant non-cook, leaving the grocery shopping and apron wearing to the rest of my family: my mom and dad, who prefer cooking at home to restaurantgoing for health and money and ambience reasons, and my brother, who spent his early 30s learning to cook David Chang’s bo ssäm recipe while I was lying on my couch and ordering Seamless.

But why cook when you live in New York City? Why fall under the thumb of the patriarchy, which expected me to labor away at this quotidian chore, providing others meals when what I really wanted was to have them served to me? Takeout was empowerment! A feminist act! And, for that matter, a far better use of my time.

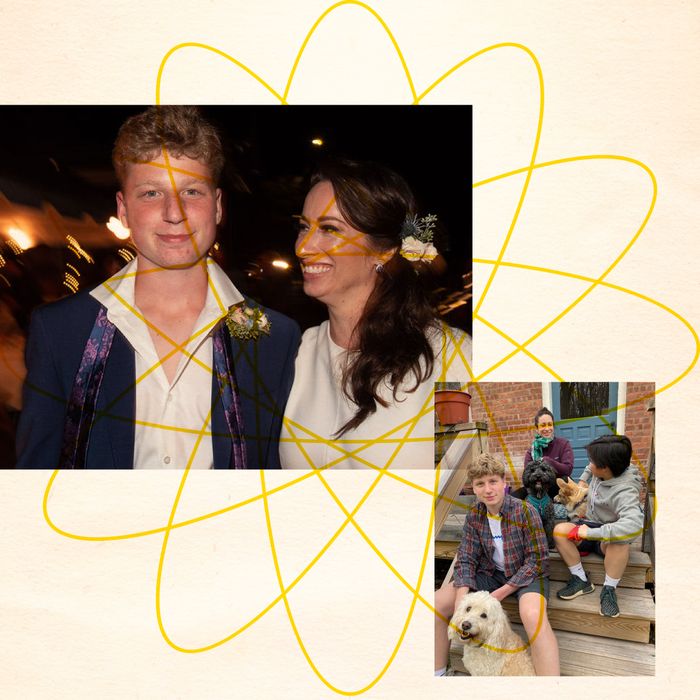

Then, in 2017, I met Ezra, who lived upstate. He had a full-fledged kitchen and a full-fledged adult life, including two kids: a daughter, Daisy, who was in college, and a son, Quinn, who was 14 years old. Ezra and his ex shared custody, trading weeks on and off, which meant, as we began to get serious, there was also a teenage boy around a lot of the time. My life in the city hadn’t exactly prepared me for this. But at least there were some basics you could rely on: People needed to eat, and watching TV was a good thing to do that didn’t require much more than being together in the same room.

So we started doing both. I think the first thing Quinn and I cooked together was nachos. Tortilla chips, covered in chopped onions and cheddar, thrown onto a pan and into a hot stove until the chips were crisp and gooey with melted cheese, the sharpness of the onion the exclamation point on the sentence. We devoured them while watching The Good Place on one of the nights that Ezra worked late, picking the burned cheese from the foil and licking our fingers, and I felt somewhere between parent and friend, roommate, and babysitter. Whatever it was felt nice. So we did more of that. Sometimes we went out for pizza, or burgers, or sushi. Sometimes Ezra cooked: Quinn loved barbecue chicken, potato pancakes, roasted broccoli, tacos, chicken fingers, and King’s Hawaiian rolls.

My relationship with Ezra evolved into moving in together and marriage, which made my relationship with Quinn official: I was a stepmom, but what did that mean? I didn’t want to be a rule enforcer or a taskmaster; I feared becoming anything remotely approaching the evil stepmonster trope. Quinn didn’t require a lot of rule-enforcing anyway, and he wasn’t a child who needed help with his homework (okay, I did edit a few of his essays) or bedtime stories. Soon, he was driving and didn’t need rides to school or soccer. I could buy him meals, sure. Or maybe I could learn to cook. I could make so much more than nachos, I figured, if I really tried.

It was as if I’d been possessed by the spirit of Julia Child. I bought eight-pound pork shoulders and slow-cooked them all day for pulled pork, or made them into the bo ssäm I’d seen my brother put together years before. I made spinach lasagnas with bechamel sauce and hand-dipped ricotta; I roasted chickens with sides of rosemary-infused croutons and smashed potatoes and then made stock with the carcasses. Quinn would wander through the kitchen, asking, “What’s for dinner?”; he’d lift the cover from a simmering pot and inspect the contents. “Oh my God, that smells so good,” he’d say, and I’d swell with pride but try not to show it. Ezra, shocked that I’d morphed into a person who made her own crackers from sourdough starter, started to buy me cookbooks, which I pored over like they were research for my next novel. I made zucchini soufflés, Marcella Hazan’s bolognese, oven-roasted chicken shawarma and fried eggplant, a 16-layer crepe cake for Quinn’s birthday. “This is like food in a restaurant,” Quinn would say. I’d say something self-deprecating, but inwardly I was thrilled.

Meanwhile, Quinn actually got a job at a restaurant. He started as a busboy, but when the pandemic struck, he moved to the kitchen and learned how to cook. He’d come home and we’d talk about whatever he was making: He created a smashburger that ended up on the restaurant’s menu with his name attached to it. He’d show me recipes and YouTube videos for things like birria tacos and cloud bread; we discussed the joys of chile crisp and rendered pork fat. He developed a signature egg dish, which involved scallions and cream cheese and soft-cooked eggs, a concoction you’d dip charred bread into. “Do we have chives?” he’d ask, pulling things out of the refrigerator. “What are you making?” I’d say, and watch as he did his thing.

During that calmer period of the pandemic in the summer of 2021, when we actually ventured out into the world again, Quinn graduated from high school. To celebrate, I made us a reservation at a really nice French restaurant, where we feasted on escargot and crusted goat-cheese salad. Quinn got duck confit, which elicited the reaction I always waited for upon his and his dad’s first bite of food: a sigh of delight indicating a successful dish. Days later, we were still talking about that meal.

The summer went by in a blur, and at the end of it, Quinn left not for college but a road trip. His eventual goal was California, but he’d take his time, stopping wherever he felt the urge. He worked as a dishwasher at a lodge in Michigan for a few weeks, then moved on. He sent me a picture of cheese curds he’d bought in Wisconsin, which he wished he could make something with, except he didn’t exactly have a kitchen handy. Meanwhile, we were redoing ours at home. “Just wait till you see the oven!” I told him, texting him Snickerdoodles I’d just baked. “I can’t wait to cook on it,” he’d say.

By December he’d made it to California, and he and I had worked out a scheme: He and a friend would drive back East in her van for the holidays so he could surprise his dad, and then, after Christmas, I’d fly him back to L.A., where he’d left his car in long-term parking. I had some concerns — winter weather and icy roads; don’t drive too fast! — but also, most importantly: What should we have for Christmas dinner?

“I’m thinking mushroom bourguignon over polenta,” I texted him. “Duck confit!” he wrote. “You might have to help me,” I said, and he added a heart to my text. And, to his credit, he did drive me to the grocery store to find the duck legs, though I ended up doing most of the cooking on my own.

The truth is, I didn’t mind one bit. Far from being a tool of the patriarchy, a method of controlling my time and energy, cooking, I had found, was a kind of power. It could transform lives, build relationships, or just turn a night into something special. Sharing food gave us a space to unite and communicate, even when it was just nachos in front of a TV on a weeknight.

Stepmotherhood was complicated, and I wasn’t always sure I was doing it right, but with cooking, it was easy. You didn’t have to say a word: You just put your love on a plate and let them eat.

https://www.thecut.com/2022/03/cooking-family-bond-stepmom.html

2022-03-08 14:00:16Z

CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LnRoZWN1dC5jb20vMjAyMi8wMy9jb29raW5nLWZhbWlseS1ib25kLXN0ZXBtb20uaHRtbNIBAA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Essay: Cooking As Family Therapy - The Cut"

Post a Comment